Stopping about 500 metres from the summit, I prop my bike up by its pedal on the edge of the pristine asphalt. Hot tea and an end to the struggle wait just around the next corner, no more than five minutes of hard pedalling away, but this view, this moment are both too good to rush away from.

Peaks draped in snow line the horizon ahead of me. Behind, the vast valley up I’ve just cycled through sprawls out below to the left, and the smooth-as-Silverstone road surface glistens in the warm sun. Cycling rarely gets as good as this. For several precious minutes I savour the setting, before hesitantly remounting my bike and continuing on, fatigue returning to my legs almost instantly.

I’m no stranger to cycling up big hills, but this is no ordinary climb. This is Taglang La, the formidable final pass on the majestic 490km mountain highway from Manali to Leh, in the Indian Himalayas. The ascent is 14 km long, which is far from abnormal. But what makes it stand out is a picture-perfect backdrop and the fact that the summit eventually arrives at a lung-emptying 5,328m, a good half-kilometre higher than the top of Mont Blanc.

I’d say it was like cycling the Alps on steroids, but steroids would make things easier. The first 8km of this route wind up the side of the valley on a gravel road. It’s tough going. The final 6km stretch, however, is on newly laid tarmac, and is so unblemished that the treads of my tyres hum as they roll over the surface.

Taglang La somehow gets even better on the descent down the opposite side. The already incredible scenery only improves as the heart of the Stok range comes into view, and the road itself is the stuff of dreams: 10 hairpins and a multitude of other sweeping corners spread over 31 blissful kilometres.

By the time the road finally reaches the valley bottom, the temperature is a good 20 degrees warmer and my eyes are watering with exhilaration. I’m in little doubt that this has been the best climb I’ve ever cycled, and the Manali to Leh Highway is only just getting started.

Amazingly, given how epic this climb is, few cycling aficionados in Europe have ever even heard of Manali to Leh, let alone put it on their roads-to-ride bucket list. Only a few hundred people tackle it each year.

Road of dreams

The road was built – or rather cut out of the mountainsides – by the Indian Army’s Border Roads Organisation (BRO) in 1987 as a means of connecting the provinces of Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir, predominantly for freight transport. Such is the grandeur of the mountains, however, that two-wheeled tourism also caught on, as motorbikers and, more recently, cyclists, were lured by a spectacular route dubbed the ‘Highest Motorable Road in the World’.

In total, the route includes five passes—two of which stand over 5,000m—has an average elevation of over 4,000m and is only open from June to September because of the winter snow. New asphalt has been and is being laid on many stretches, but well over a third of the route is on broken road, varying in quality from forgiving to worthy of a downhill mountain bike race.

“There is a lot of climbing. 8,500 metres in total—almost the height of Everest”

While most people ride hardtail mountain bikes as a result, cyclo-cross bikes also hold their own on the descents and offer far faster and more comfortable climbing. And there is a lot of climbing: a biblical 8,500 vertical metres in total—almost the height of Everest.

Couple that with the extreme altitude and progress is slow. It ends up taking nine days to ride from Manali to Leh, as we cover an average of 55 km in a six hour day. Following a two-day bus ride from Delhi to Manali and a short warm-up ride, we start the journey under the thick mist of the late monsoon, pedalling 35 km away from civilisation to a campsite halfway up the first major climb, the 3,979m Rohtang Pass.

This is the baby of the route, but because of the need to acclimatise to the altitude, taking your time is as integral to this journey as inflating your tyres and filling your bottles. So we tackle it at a slow pace, allowing our bodies to adjust steadily to the ever-thinning air.

As the road snakes its way up grassy valley sides and around countless hairpins, it feels like I’m riding the Col du Tourmalet or Col du Galibier in Europe. But when we finally reach the top, the scene is distinctly Himayalan.

The Rohtang Pass and its neighbouring peaks are so high that they create a ‘rain shadow’, trapping the monsoon clouds in the south and leaving everything north far more arid. The effect is that the skies suddenly clear as we crest the pass, and we get our first sight of the snow-capped 6,000m peaks we will spend the next week or so slaloming through.

Before then comes the pleasure of a descent as spectacular as Taglang La. The southern flank of the Rohtang is a joy to climb but the northern side is a step up again. Its 24 hairpins, offering mountainous views across the valley of the Chenab River make for a cycling experience so rich, and so idyllic that I can’t help but laugh at my fortune to be riding here.

Brutal cycling beauty

Over the next day and a half we follow the Chenab and then Bhaga River, before leaving their raging torrents behind to climb steadily to the marvellously named village of Zingzingbar, which sits at the foot of the second high pass, Baralacha La.

‘Village’, however, turns out to be a generous description. The winter here is too brutal and the land too unyielding for permanent settlements, so Zingzingbar and the other staging posts between Manali and Leh are instead collections of five or six guesthouses-cum-restaurants-cum-grocery shops made from rocks and sheets of tarpaulin. They are not much to look at, but the people inhabiting them are welcoming and the hot tea they serve is refreshing.

Baralacha La stands at 4,850m—a significant increase on the Rohtang—and we inch up its gentle slopes under heavy but dry cloud cover, passing by the turquoise Suraj Tal lake before reaching a barren summit covered with Buddhist prayer flags.

Since the Rohtang, the landscape has been dominated by snowy peaks standing over us. But after Baralacha La, the road dips down into a valley cut by the Tsarap River that looks more like Mars than the Himalayas. The towering scree-lined peaks on each side change gradually from black to terracotta and finally to egg-yolk yellow over the course of ten otherworldly kilometres.

We reach a plateau housing a tent colony known as Sarchu, where we stay for the night, before continuing along the sculpted banks of the Tsarap the next morning. This takes us to the foot of one of the most stunning sections of road—not just on this route, but potentially in the world.

“It’s like the 21 hairpins of Alpe d’Huez... but more tightly packed.”

The Gata Loops are a series of 21 hairpin bends winding 10km straight up the valley side. It’s comparable to the iconic Alpe d’Huez climb in France, which also has 21 hairpins. But here they are more tightly packed and the backdrop is far more expansive.

Until this point I have been taking pictures incessantly, every single view worthy of capture, but the cycling on this stretch is too idyllic to keep stopping, so I climb it one go and in such a heady state of enjoyment that I forget what altitude I’m at, push too hard and am totally spent by the top.

A stop for lunch fails to bring me back around and so I limp painfully over the third of the high passes, the Nakeela Pass, which follows immediately after the Gata Loops and tops out at 4,738m.

- READ NEXT: Best Bikingpacking Gear

After a descent on a broken road down the opposite flank and a night beside another wonderfully named ‘village’, Whiskey Nullah, at 4,800m, I’m feeling fresh again the next morning. It’s just as well, because today’s 75km stage is the longest of the trip and we have to climb above 5,000m for the first time to reach the summit of the fourth pass, the 5,059m Lachalang La.

It’s freezing at the top, so we pile on layers and then hurtle down a gravelled descent into yet another new landscape, this time a narrow gorge hemmed in on each side by pillars of yellow rock that look like they have been poured like concrete from above.

The highway then rears up once more on to a wide and flat corridor through the mountains known as the More Plains, where a 40km straight on freshly laid road awaits. Better still, we’re blessed with a welcome tailwind. My tired legs breath a sigh of relief.

The following day takes us up the Taglang La before we descend 1,800m all the way down to the quiet village of Lato, passing Tibetan-style settlements along the way as we leave the Zanskar range behind and enter the deeply Buddhist region of Ladakh.

Our final day into Leh is yet another gem. Our route runs alongside the mighty Indus River in the early stages of its journey from the Himalayas to Arabian Sea. We make a final stop off at the Thiksey Monastery, a Buddhist monument that rivals Lhasa’s Potala Palace—the original seat of the now-exiled Dalai Lama—for size and splendour.

King of the mountains

Leh itself is a fusion of old world and new. The Namgyal Tsemo Monastery, which dates back to 1430, towers above a bustling city packed with restaurants and shops hawking SIM cards, travel agencies offering rafting trips on the Indus, and guides selling treks into the Stok range.

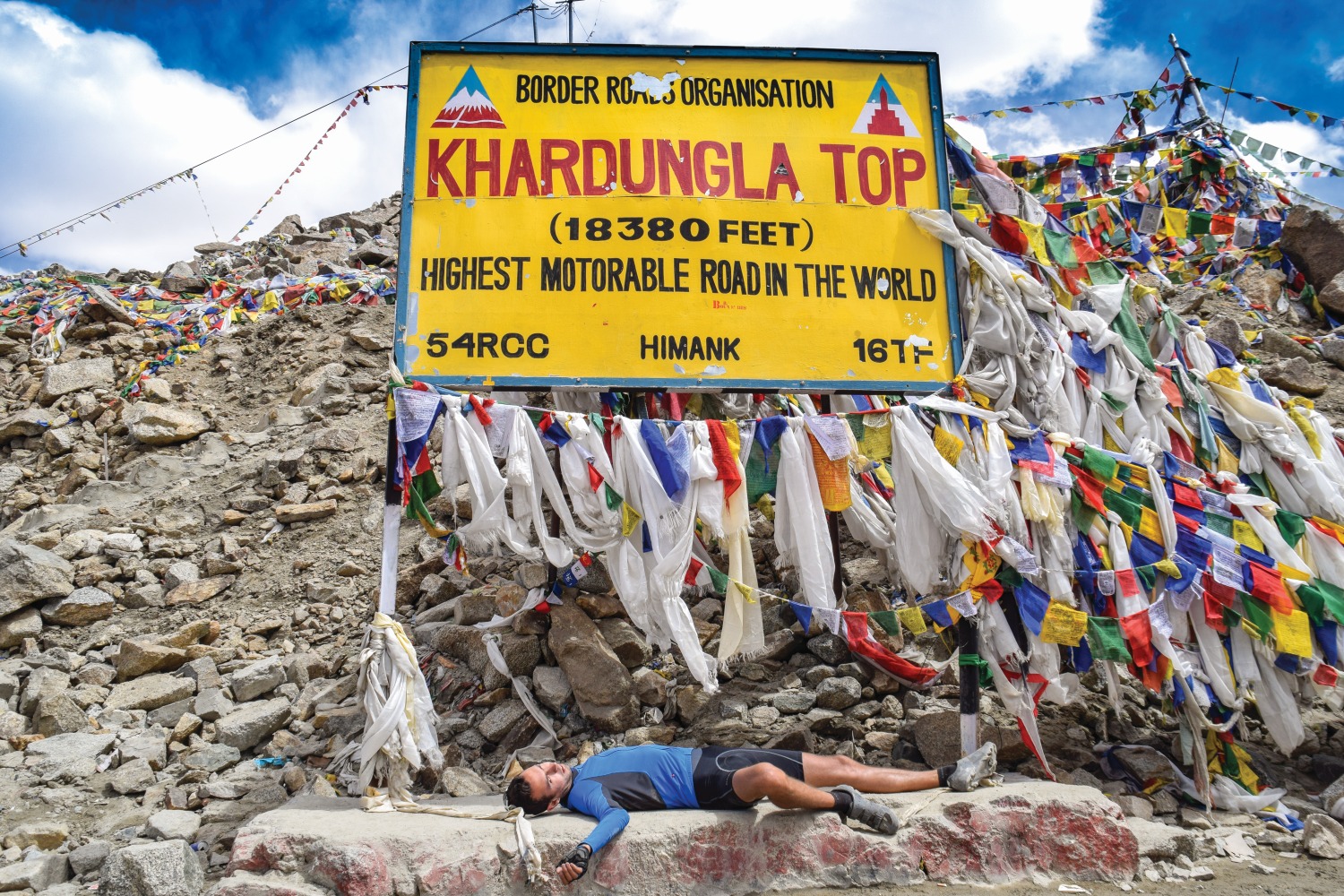

It’s a welcome return to the real world after the isolation of the Manali to Leh Highway, and an ideal place to rest up for a day—because we’re yet to embark on the ultimate challenge of the trip. The colossal climb of Khardung La, which separates Leh in the south from the Nubra valley to the north, isn’t part of the main route but most people tag it on at the end due to its growing fame and notoriety.

"...each turn of the pedals is a battle, a small, painful victory within a wider war of brutal attrition."

The BRO claims it is the single ‘highest motorable road in the world (it isn’t) and that the top stands at 5,600m (it doesn’t), but the actual numbers are nevertheless eye-watering—the summit is 5,359m and the road ascends more than 1,800m over its daunting 39 km distance from the start point in the centre of Leh— and the climb is unquestionably one of the toughest on the planet.

The fastest time it has been ridden on Strava is just over three hours, but four and a half to seven is a far more realistic guide for those blissfully ignorant enough to attempt it. The first 25 km are on decent asphalt and are a pleasure to ride, as they wind their way up the flanks of the mountain that the pass straddles. But after an army camp 14 km from the top, all hell breaks loose. From here on in, the road is simply savage—so broken, rocky and dusty that it takes immense concentration just to maintain forward momentum along its surface.

Inside the last 10 km I have to stop every kilometre to get my breath back. It feels like my legs are made of lactic acid, and each turn of the pedals is a battle, a small, painful victory within a wider war of brutal attrition. And then, just when I feel like I can’t possibly carry on, the road finally flattens out. I turn a corner to find prayer flags fluttering and the summit sign standing tall.

I’m completely spent as I dismount, but views of snow-capped peaks in the distance, and the entirety of the Stok range stretched out in front of me are a more-than-handsome reward for having risen to this epic challenge.It takes two and a half hours to descend all the way back down into Leh, where I can’t wait to get off my bike. But when I pack it away that night, ready for a flight back to Delhi, it’s with a deep sense of sadness. I know that the best ride of my life has come to an end.

- READ NEXT: Best Cycling Holidays in Europe