I’ve been fascinated with Japan for my entire life. It started with computer games (Streetfighter) and toys (Transformers), then the samurai and martial arts. Now, as an adult, I love it for food, sake, whisky and anime.

Culture is what brings most people to Japan, but its northernmost island, Hokkaido, has become a winter-sports nirvana over the years, thanks to epic amounts of annual snowfall. More recently, some of the powder-hounds who flocked here realised that Hokkaido could be a year-round adventure destination, and now the local tourist industry is waking up to that demand.

So, when I get an email asking if I’d like to visit Japan, I skip Tokyo and head straight for Asahikawa, Hokkaido’s second city and the gateway to Daisetsuzan National Park. The grand attraction is Asahidake, the island’s tallest mountain, and an active stratovolcano.

From the top cable car station, a 30-minute loop gets me up close and personal with fumaroles belching sulphurous steam, and it’s another two-hour trek to the peak. But the real joy is the alpine traverse to Kurodake, along the edge of the vast, steaming, Ohachidaira crater, followed by moorlands of alpine flowers. Apparently it can get busy on August weekends up here, but during my walk in late September, I only pass four people during the five-hour walk between peaks.

Mt Kurodake is capped by a shrine, shaped like a toru gate. As I approach, a young couple walk up to it, bow, clap twice and then bow again. They gesture for me to do the same and, after I clumsily copy their actions, they give me an enthusiastic thumbs-up. Then it’s another hour to the Kurodake Ropeway, and the cable car to Sounkyo Gorge.

Multi-day hikes do exist in Hokkaido, but the details are hard to come by. The information centre near Asahidake has a fantastic 3D model of Daisetsuzan, but no maps that cover multi-day routes, nor details about huts and campsites.

“We don’t like to give out too many details,” says Michiko Aoki, a local mountain guide, “In case people underestimate the risks and do it by themselves. So we encourage them to go with a guide.”

The best source of information in English is the website HokkaidoWilds.org. It was set up by a New Zealander who has lived in Hokkaido for over a decade, and it is full of itineraries, links to downloadable maps, and information about the hut system. Even if you go with a guide, Hokkaido Wilds is a great source of inspiration.

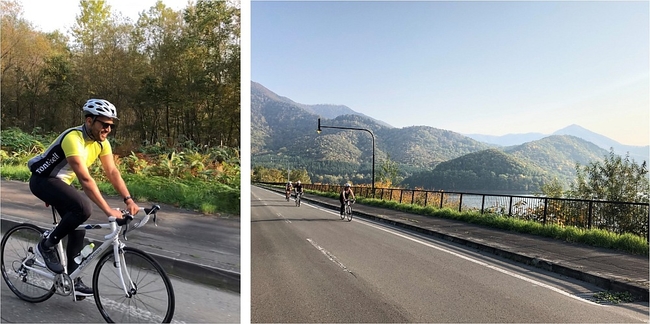

It also features cycling itineraries. Hokkaido’s low population and wide, well-maintained roads, make it a cyclist’s paradise. There are routes along the coast, and challenging climbs through the mountains, but my favourite is along Lake Kanayama near Minamifurano, which I do in the company of cycling guide Tohru Sakamoto.

We stop by the lakeside to meet his colleague Shigeo Kobayashi, who calls himself ‘the genie of your journey.’ He certainly lives up to his name, having set up a magical spread of fruits, savoury snacks and freshly-brewed matcha tea for our arrival.

“People come from all over the world to cycle across the island,” Shigeo says, “Most bring their own bikes, so Tohru guides them, and I bring the support vehicle. But, just because cycling is exercise, doesn’t mean that it can’t be enjoyable. We Japanese are very efficient!”

On his table is a model of an Ussuri brown bear, a smaller relative of Alaska’s grizzly and the icon of Hokkaido. They live throughout the island, but their greatest concentration is on Shiretoko Peninsula, which divides the Pacific Ocean from the Sea of Okhotsk. There’s no human habitation in this forested national park, and it’s barely two kilometres from the sea to the top of its highest mountain.

Biologist and guide Mitsuki Matsuda has been studying the bears here for decades, and he takes me along an old timber trail from the visitors’ centre, to sheer cliffs of hard volcanic rock.

“There’s about 300 bears on this peninsula,” he says, “But don’t worry. They are very shy, and usually run away from humans. I’ve only been attacked once.”

I’m not sure if I’m reassured, a feeling that grows when I spot a tree with deep claw-marks, and a half-eaten salmon in the middle of a path. There was nothing here when we passed this way five minutes previously, so bears must be nearby. We hide on a bridge overlooking their salmon-fishing ground, but the bears stay hidden, and we return to the nearby town of Utoro.

I’ve been looking forward to this part of the trip as much as any other, because Utoro is the home of Namishibuki, a Michelin-recommended noodle-bar. I’m not disappointed. Their tonkotsu is made from slow-boiled pork bones and miso, with melt-in-the-mouth roast pork and home-made noodles. It’s warming, delicious, and the best ramen I’ve ever eaten.

My Hokkaido adventure finishes with a canoe on Lake Kussharo, which is actually the caldera of an ancient volcano. All that heat has its advantages, in the shape of onsen – natural hot springs. Japan is full of onsen-resorts, in which the hot water is piped into hotels. But, if you know where to go, you can still find open-air onsen.

After a barbecue dinner of wagyu beef at the Wakoto Peninsula campground, I go for a walk along the lakeshore. There’s a sulphurous tarmac scent in the air, and I spot the dim lights of a public changing room to my left. Beyond it, overhung by trees, is a small pool. I take off my towel and step into the hot water. The floor is gravelly, and I slowly lower myself in until I’m sitting down, immersed up to my chest.

As my muscles unwind from a week of non-stop activity, I look up to see the Milky Way stretching across the sky. I take a sip of cold sake, and decide that Hokkaido might just be the world’s best adventure destination.

For more information on Hokkaido go to www.japan-guide.com and for glamping information go to wondertrunk.co

- READ NEXT: HIKE AND BIKE JAPAN'S QUIETER SIDE IN TOHOKU